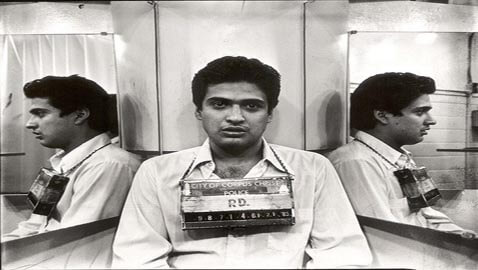

The death of man who from the time of his arrest to the death-row kept crying “I am innocent” is heart-breaking. For Reverend Carroll Pickett, DeLuna was the thirty-third person he eased through his last day. Pickett oversaw sixty-two more executions, in total ninety-five, but it was DeLuna’s case that led him to seek psychiatric help. For you could see truth in the man’s eyes crying innocence, the truth that the state system of Texas steadfastly refused to recognize.

DeLuna told the law enforcement that Carlos Hernandez was the actual killer, but the prosecutor said that the killer named by DeLuna was a “phantom.” Evidence uncovered through the years show that Hernandez was not only real, but he was well-known to the police, let off time and again over serious crimes and both the police and the prosecutors were aware of the crimes and history of Hernandez, but they chose to execute Carlos DeLuna in his place. Crying “I didn’t do it, but I know who did” did not help DeLuna, because the state of Texas clearly did not want the real criminal in the net as shown in the following facts. DeLuna was charged with the murder of a woman whom he did not even know and killed in prison.

The real killer, Carlos Gonzales Hernandez Jr. spent most of his 45 years on earth committing crimes for which he was never punished or barely punished if at all. In 1971 he was convicted of ‘negligent homicide’ for killing the boyfriend of his sister. Hernandez’s sentence was suspended and he did not spend any time in jail. In 1972, Hernandez was sentenced for twenty years each for three armed hold-ups, amounting to sixty years. Texas decided to parole him after five years, because obviously, someone needed him outside. Immediately after, in 1979, Hernandez was arrested for killing Dahlia Sauceda in front of her two-year old daughter and carving an “X” on her naked back. Prosecutor Kenneth Botary released him and went after another man who was eventually acquitted. Hernandez was once again arrested in 1986 for the killing, but by that time, conveniently, the prosecutor had ‘misplaced’ key evidence and the charges were dropped. Then in 1989, Hernandez assaulted Dina Ybanez with a seven inch knife. The court gave him a ten-year sentence. Texas paroled him in one and a half years.

So, Hernandez killed Wanda Lopez in 1983, and the law enforcement and the prosecution went after ‘childlike’ Carlos DeLuna, had him sentenced for execution, and killed him in 1989 by injecting poison. What struck Reverend Pickett was DeLuna was not concerned with death but whether the injection would hurt.

This is the first time in its 45-year history that the Columbia Human Rights Law Review has devoted an entire issue, Issue 3 of Volume 43 to a single topic, the wrongful execution of DeLuna, and the hours of video recordings, evidence, and documents presented by the team of professor Liebman.

After a sixteen year hiatus, Texas resumed executions in 1982. Since then, there have been 482 executions in Texas, four times more than any other state in the USA.